Learn the science behind perfecting your taper with help from CTS coach, Jim Rutberg.

By Jim Rutberg, CTS Coach

Tapering is a mixture of art and science, meaning you’re going to want to start with solid evidence-based steps but you must also understand how to evaluate your progress and make adjustments. As I did with a recent piece on heat acclimation, I’m going to approach the subject by answering the questions CTS Coaches get most frequently about tapering.

The simplest way to think of a taper is as a reduction in training load that reduces fatigue but incorporates enough training to preserve fitness. It is not a complete cessation of training or a week of zero exercise leading into an event. If you just stop exercising, you will get plenty of rest but you’re more likely to feel sluggish and stiff by race day. A taper keeps you moving and helps you sustain your exercise routines but lowers the total daily and weekly training workload so that recovery takes priority.

Two weeks is the rule of thumb for an ultramarathon taper. The optimal duration of a taper is a balancing act between resting as long as possible to reduce fatigue and let your fitness shine versus maintaining enough training stimulus to keep fitness from starting to decay. For most amateur and age group ultrarunners, there’s no benefit to making tapers shorter than 10-14 days or longer than 21 days. It can be detrimental to start your taper too early and reduce training load for too long before your event. Your fitness can start to decay, especially because the training closest to race day is often easy to moderate intensity running and hiking that is very event specific.

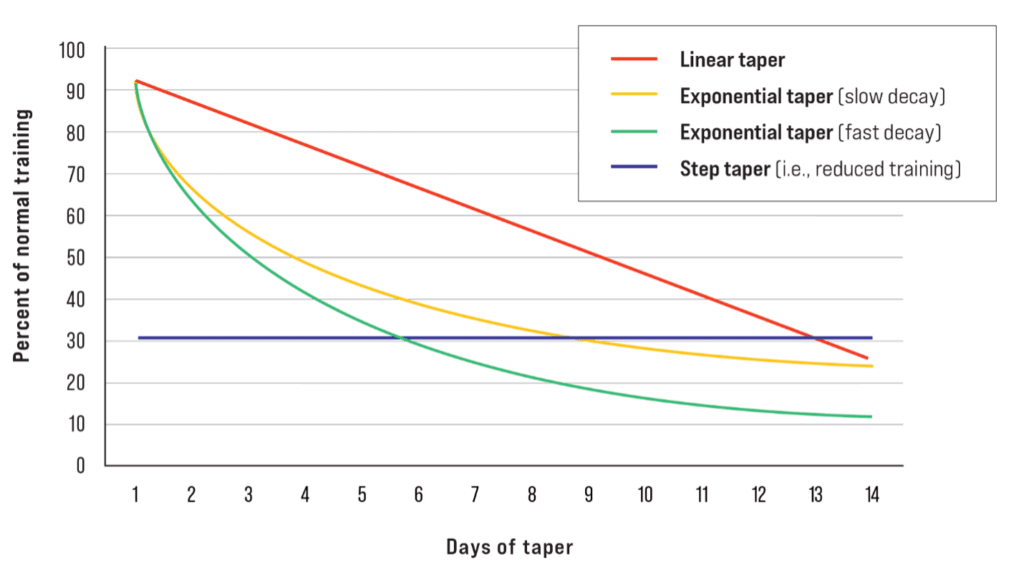

There are four main types or methods for tapering: Linear, Step, Fast Decay Non-linear, Slow Decay Non-linear. (read more about taper models) Jason Koop, the Head Coach for CTS Ultrarunning and author of “Training Essentials for Ultrarunning”, often recommends a 2-week Fast Decay Non-linear taper, which means volume should decrease very quickly at first and then level off toward the end. In practical terms, if you’re running 10 hours per week before the taper, you should reduce that to four to five hours (40 to 50 percent of normal training volume) the first week. This should reduce to two to three hours (20 to 30 percent of normal training volume) the second week. If there are remaining days at the very end, drop to <20 percent of normal training volume.

To accomplish the goal of reducing training workload, you want to make individual workouts shorter but maintain your normal training frequency (or just reduce it by one workout per week). Your training pattern should remain relatively constant. You’re accustomed to that routine and the training, recovery, and eating patterns that go along with it. There’s no reason to disrupt all of that, just make the individual runs shorter to accomplish the fast decay non-linear reduction in training workload.

Yes! Incorporating intensity into your taper is essential for success. Although it may seem counterintuitive to keep doing intervals when the goal is to rest and freshen up, it works because it doesn’t take a high volume of intensity to maintain the fitness you already have. You’re just giving your body enough stimulus that it doesn’t lose the adaptations you worked so hard to gain. This means maintaining the type of intensity (e.g., TempoRun intervals) you’ve been doing as you go into your taper, but reducing the amount of time-at-intensity. So, if you had been doing four by 10-minute TempoRuns for a workout, during Taper Week 1 you would do three by five-minute TempoRuns. In Week 2 you would do two by five-minute TempoRuns (25 percent of the normal TempoRun volume).

On average, probably about 1.5-2%. If you were able to do everything perfectly and all the stars aligned, researchers Mujika and Padilla found that a properly constructed taper can improve performance by up to 3% (compared to no taper at all). Pragmatically, the issue is that the stress and focus required to maybe wring that extra 1-1.5% improvement out of your taper can be counterproductive and cost you more than you could potentially gain. So, for most amateur and age group ultramarathon runners, the best advice is to aim for a reasonable taper, don’t let tapering add more stress than it saves, and expect about a 1.5-2% bump in performance.

Aim to keep your eating and sleeping behaviors consistent as your taper progresses. Some athletes will dramatically reduce their total daily energy intake as soon as their training volume drops at the beginning of the taper. Don’t do that, at least not proactively. You may not feel quite as hungry because you’re not training as much, but eat to satiety and keep your macronutrient composition consistent with the weeks leading up to your taper. You need the energy to fuel your recovery and create those final adaptations that can happen now that daily training workload isn’t as high. If you’re tracking calories, keep in mind that total daily caloric intake will likely dip from consuming fewer nutrition products during runs. You don’t need to increase meal sizes to replace those calories.

Similarly, keep your sleep pattern and duration relatively consistent. There’s some evidence that increasing nightly sleep duration by about an hour for 7-10 days before an expected bout of sleep deprivation can help with physical and cognitive performance in a fatigued state (e.g., 3 a.m. direction finding or decision making at an aid station). But beyond that, the biggest key is to minimize sleep disruptions from anxiety, travel, packing and repacking you gear, and fretting about your race.

You’re not alone. Those feelings are so common we have a name for it: taper tantrums. Athletes who are accustomed to twice as much training load suddenly have idle time on their hands and minds, along with plenty of energy. Instead of settling into the quiet, your brain invents things to worry about or new tasks to accomplish. Workouts that are supposed to be shorter and include only a little intensity turn in to fitness tests because you feel so good and want to see what you can do. These are the behaviors that derail a well-planned taper, and it can take experience and repetitions to reach the point where you recognize you’re engaging in taper tantrums.

Reference:

Mujika, Iñigo, and Sabino Padilla. 2003. “Scientific Bases for Precompetition Tapering Strategies.” Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise 35 (7): 1182–1187.

What do you recommend to do or think about in lieu of experiencing ‘taper tantrums’? What activity would be fitting for this time – perhaps volunteering for something that doesn’t require much on-feet activity? I do like the article & will help me but would have liked suggestions of activity to replace the workout pieces you’re not doing. Thanks

I volunteer at local shelter and walk dogs. Great taper activity. Time on legs and feet but not strenuous, plus helping dogs get out that need walks