Learn about the basics of effective heat training from the experts at CTS.

By Jim Rutberg, CTS Coach

Heat acclimation or heat training is one of the most effective, economical, and popular training interventions for trail and ultramarathon runners. In a world where socioeconomic factors can restrict which athletes have access to the latest wearable devices, recovery tools, and high-tech gear, heat training is an accessible tool almost anyone can benefit from. You just need a hot environment, whether that’s the great outdoors, a heated room, or a few layers of warm clothing. The more nuanced aspects of heat training are scheduling heat exposures for maximum effect and determining the best time to start and end your heat training protocols.

As with so many areas of sports science and training, you can explore the basics of heat training or do a deep dive into the grittiest of details. I’m going to aim for the middle between those extremes by answering the questions CTS Coaches get most frequently about heat training.

Heat acclimation is the process of adapting the body’s cooling mechanisms to overcome the challenge of dissipating heat in a hot environment. Most of the adaptations relate to sweat:

Heat is the enemy of endurance performance. As you’re running, muscles generate a lot of heat that must be dissipated so your core temperature doesn’t rise out of control. For optimal health and performance, core temperature is tightly maintained within a narrow range, approximately 36-40 degrees Celsius (97-104 degrees Fahrenheit). Bad things happen when athletes overheat, including confusion, agitation, slurred speech, nausea, and vomiting. And that’s before you reach the level of heat stroke, characterized by both high core and skin temperatures and often a cessation of sweating. At body temperatures above 104 degrees F people can suffer from organ damage or even die. Right from the beginning of the hellish descent to heat stroke, just at the point of mildly overheating, running performance diminishes dramatically.

Heat acclimation ramps up the body’s cooling mechanisms and adaptations that make athletes more resilient in hot environments. The adaptations listed earlier improve performance by allowing runners to adequately dissipate heat while sustaining moderate to high intensities in hot conditions.

One of the most interesting new ideas in sports science is the opportunity to use heat training as “the poor person’s altitude training”. It is so termed because altitude training is typically an expensive venture, requiring a prolonged trip (3 weeks minimum) to a destination above 2000 meters elevation or the purchase of an altitude tent. In contrast, heat training can be accomplished at home with a space heater and/or a few layers of clothes.

A potential reason heat training and altitude training may result in similar increases in oxygen-carrying capacity starts with blood plasma volume. Increased plasma volume is one of the first responses to exposure to either heat or high altitude. This increase in plasma volume causes a reduction in hematocrit, which is the number of red blood cells in a given volume of blood. The kidneys are sensitive to red blood cell concentration and read the increased plasma volume as a dilution of the blood. They respond by releasing more EPO to stimulate red blood cell production, no matter whether the stimulus came from altitude or heat exposure. (Rønnestad et al., 2021; Oberholzer et al., 2019).

Is heat training as effective as a prolonged exposure to altitude? That’s a harder question. Individual responses vary for either intervention, meaning some people experience a bigger boost in red blood cell count than others. Altitude training can also be disruptive to an athlete’s progress because training intensity must be reduced to account for slower recovery at altitude.

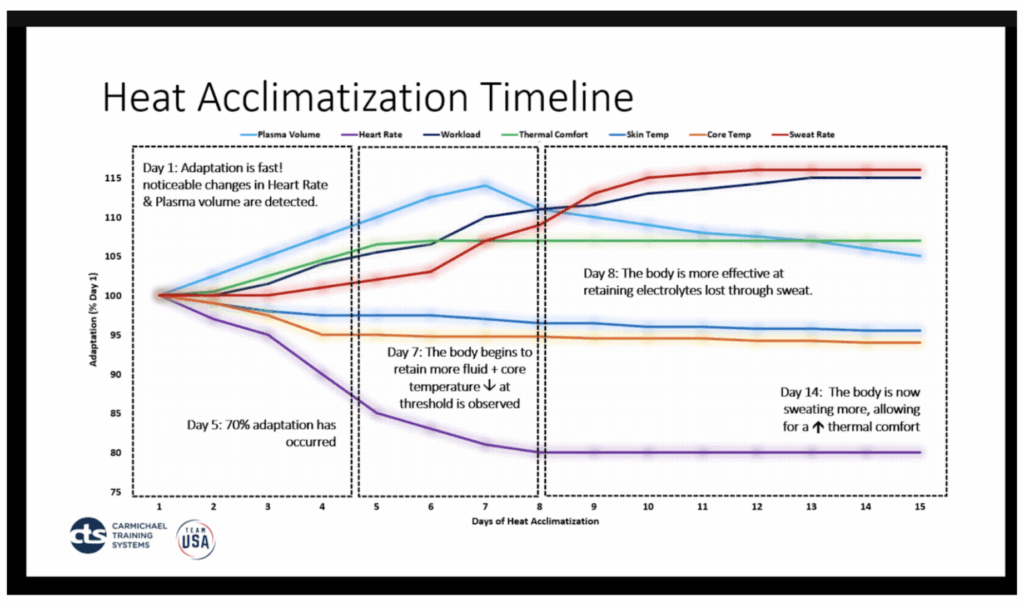

The short answer is you need to spend time in hot conditions. The process of heat acclimation takes about 10-14 days, as illustrated in the figure below from a presentation by CTS Coach and US Olympic Committee physiologist Lindsay Golich. This will mean daily exposures lasting as little as 15-30 minutes.

In terms of a hierarchy of preferred heat exposure methods, my CTS Ultrarunning colleague Jason Koop recommends a dry sauna as his first choice, followed by a hot water immersion bath, and finally a wet sauna. For active heat exposures, he recommends exercising in a heated room over exercising in multiple layers of clothing.

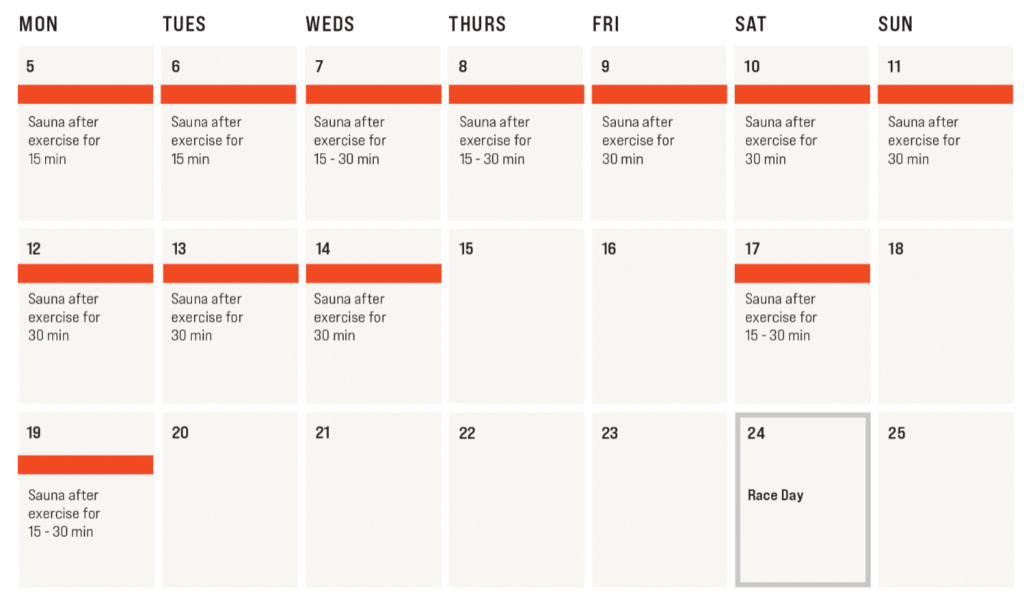

If you only have time for one round of heat training, start about three weeks out from your event. The protocol below incorporates daily passive sauna exposures for 10 days, followed by “maintenance sessions” every few days. The reason there are no sauna sessions in the final week is because heat exposure is a stress, and in the final week it can hinder an athlete’s taper.

If you have more time to start a heat acclimation protocol earlier, you can use this “Repeated Exposure Protocol” that starts about 6 weeks before an event. The benefit of this approach is that there is less risk of an adverse effect on your training or recovery in the immediate leadup to your event.

Emerging research shows that the physiological adaptations to heat acclimation gradually decay in two weeks after the cessation of heat training (Cubel et al., 2024). In this study, subjects achieved the maximum adaptations to heat training after three weeks of daily heat exposures, and a subsequent two weeks of additional heat training did not result in additional benefits. In other words, more is not necessarily better and there doesn’t appear to be compelling evidence for ongoing heat training. It’s best completed as a timely intervention with subsequent maintenance sessions about once every three days.

References:

Cubel C, Fischer M, Stampe D, Klaris MB, Bruun TR, Lundby C, Nordsborg NB, Nybo L. Time-course for onset and decay of physiological adaptations in endurance trained athletes undertaking prolonged heat acclimation training. Temperature (Austin). 2024 Aug 1;11(4):350-362. doi: 10.1080/23328940.2024.2383505. PMID: 39583901; PMCID: PMC11583594.

Oberholzer L, Siebenmann C, Mikkelsen CJ, Junge N, Piil JF, Morris NB, Goetze JP, Meinild Lundby AK, Nybo L, Lundby C. Hematological Adaptations to Prolonged Heat Acclimation in Endurance-Trained Males. Front Physiol. 2019 Nov 1;10:1379. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2019.01379. PMID: 31749713; PMCID: PMC6842970.

Périard JD, Racinais S, Sawka MN. Adaptations and mechanisms of human heat acclimation: Applications for competitive athletes and sports. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2015 Jun;25 Suppl 1:20-38. doi: 10.1111/sms.12408. PMID: 25943654.

Rønnestad BR, Hamarsland H, Hansen J, Holen E, Montero D, Whist JE, Lundby C. Five weeks of heat training increases haemoglobin mass in elite cyclists. Exp Physiol. 2021 Jan;106(1):316-327. doi: 10.1113/EP088544. Epub 2020 Jul 4. PMID: 32436633.

Thanks for the clear and easy-to-understand article!

What if my event will (likely) not be hot? I’m planning an ultra in Illinois in November. Would heat training still benefit me?

Hi there, and thanks so much for sharing that info. It’s amazing to think that regular sauna visits can work like altitude training, helping our bodies produce more red blood cells and improving how we carry oxygen.

I’ve always found that fascinating. For many athletes, hitting the sauna every three days feels quite doable—starting with the dry heat and, once they’ve adjusted, moving on to the wet sauna.

Personally, I love the Northern European tradition. I still remember my first proper sauna session: the intense dry heat, followed by stepping under an ice-cold shower that takes your breath away. Then you rest for ten or fifteen minutes, feeling completely alive. I usually go for three to five rounds like that.

It’s not just relaxing—it’s a brilliant way to support recovery and boost performance. That’s why I often bring these practices into my sports coaching. It’s little rituals like these that can make such a big difference in how athletes feel and perform.

Hello CTS,

I live Coachella Valley where 5 months of the year it’s 100F+. Heat exposure can give you distinct advantage in hot environs. I can remember climbing a hot day up Black Canyon in a BWR gravel long course race. I’m 60+ age grouper and all I did was pass others, some walking their bikes. Obvious for me the heat exposure was a distinct advantage. Happy racing.