Ken Ward’s research on aging in ultrarunning could redefine how older athletes train, race, and recover.

Ken Ward’s interest in research is born from personal experience.

Ward started trail running in 1999 as a way to train for mountaineering but quickly fell in love with long days on the trail. At the time, ultrarunning was still a niche sport, and race lotteries were barely on the horizon. His first 100-mile race was the Western States Endurance Run (WSER), where he eventually earned the prestigious Silver Legend Award—an honor that allowed him to bypass the lottery. That opportunity helped him notch a total of 10 WSER finishes, securing the coveted 1,000-mile belt buckle.

With a PhD in analytical chemistry, Ward has spent his career working with large data sets and predictive modeling. His passion for running soon intersected with his scientific expertise when he noticed an anomaly in WSER finisher data: why did finishing rates drop off so sharply after age 65?

“Only four finishers over 70 since day one really startled me,” said Ed Wilson, a research participant and 71-year-old ultrarunner. “And the fact that all four were more fit than me was a tough read.”

While ultrarunners tend to peak later than their road-running peers—typically around age 39-41 for men and 40-43 for women—performance begins to decline more noticeably after age 50-55. After this point, speed and VO2 max steadily decrease, even as endurance remains relatively stable. This means older runners may still excel in long-distance events, but their ability to sustain high-intensity efforts or recover quickly diminishes, making pacing, fueling, and strategic race execution even more critical.

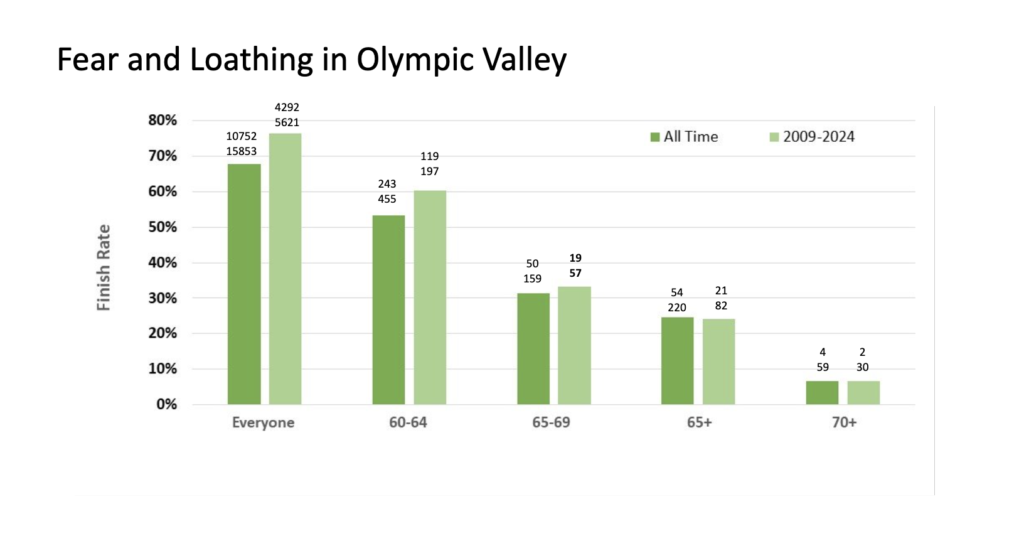

Ward turned his expertise in assessing data to WSER finishing numbers, and found that finishing rates fell sharply after age 65. In the 60-64 age group, the finishing rate is 66%, for athletes 65 and over, it’s 25%, and at 70 and over, it declines sharply to only 7%, with just four finishes in the race’s history.

“It was such a steep drop-off in the finish rates,” said Ward. “I wanted to figure out why.”

Using data from UltraSignup and Western States, Ward analyzed 35 variables to determine which most accurately predicted race outcomes. The strongest predictors—with 90% accuracy—were a runner’s UltraSignup ranking over the past three years, the distance of their qualifying race (those who qualified with a 100-miler fared better than those who used a 100K), their qualifying race performance, and their age on race day.

While some of these findings aligned with expectations, others took Ward by surprise. Contrary to the common fear among ultrarunners that one DNF leads to another, historical DNFs had no correlation with future success.

“We need to destigmatize DNFs,” said Ward. “Aging means slowing down, and that’s okay.”

Similarly, previous experience at WSER didn’t impact finish rates, a hopeful insight for runners who may only get one shot at the race due to the strict lottery and qualification system.

Ward found that even small improvements in early pacing can determine success. One of the most striking discoveries was the importance of reaching Robinson Flat (mile 30.3) at a strong pace—a near-perfect indicator of finishing success.

“You can pretty much predict success just from how fast someone gets to Robinson Flat,” Ward explained. “With that information, runners can focus on getting to that aid station efficiently, rather than worrying about running the first 50K too conservatively. If you’re slow there, you’re just not going to catch up and then you DNF.”

Ward also found—echoing what many ultrarunners are now realizing—that nutrition is more critical than ever, particularly for older athletes.

“Older runners need to fuel better from the beginning to maintain speed,” he emphasized. He encourages runners to increase their carbohydrate intake to at least 60-90g per hour and, just as importantly, practice that intake consistently in training to ensure their gut can handle it on race day.

Beyond nutrition, maintaining top-end speed is essential, even for long-distance racing.

“A lot of older ultrarunners are just trying to get miles in, but you’ve got to maintain your speed,” Ward said. He stressed the importance of incorporating strides, tempo runs, and intervals—not just logging mileage—as key to longevity in ultrarunning.

“I’m working on adding a few fast miles to test my lactate threshold without getting hurt. That’s a fine balance,” said Wilson.

Heat adaptation is another critical factor for aging runners, and emerging evidence suggests that year-round heat training can provide performance benefits, much like it does for younger athletes. While many older runners tend to stick to familiar training methods, Ward urged them to embrace evolving strategies and technologies, from super shoes to improved fueling systems, which could help extend their competitive years.

In addition to conducting research, Ward is actively working to shift systems and narratives around aging in ultrarunning.

Ward has advocated for adjustments that could support older athletes, including extended cutoffs based on gender categories or an earlier start time, similar to what has been proposed at UTMB. Additionally, he suggests allowing runners over 60 to pick up pacers earlier—currently, WSER runners can only pick up a pacer at Foresthill (approximately 100k into the race). He also supports permitting the use of trekking poles for older runners, recognizing the potential benefits for stability and endurance.

Ward is deeply passionate about his research and its potential to enhance both performance and quality of life for older runners. He’s eager to continue his partnership with UltraSignup to elevate the visibility of older athletes.

“Older runners shouldn’t quit just because they’re slower,” said Ward. “People can do these races longer, and we should be improving finish rates for older athletes.”

Ward believes that this data will be transformative for older runners who aren’t ready to hang up their shoes just yet. He hopes to keep challenging assumptsions about aging and endurance, one run, and data point at a time.

As for Wilson, he’s just happy to be there. “Lining up with the other six geezers in June will be a privilege that I may not be worthy of – just hoping to do well for the many folks that got me there.”

An earlier version of this article stated that no women over the age of 70 have competed at Western States. In fact, Gunhild Swanson completed the race at age 70 in 2015, becoming the first, and so far, only woman in that age group to finish. We regret the oversight and are honored to recognize her remarkable achievement.

Very helpful I’m 71

Thanks Ken

Thank you for the editors note regarding Gunhild’s finish! I knew it was an error as soon as I read the article. I am 57, have qualified and entered the WSER lottery 7 times maybe 8 I’ve lost count. My body wants me to give up but alas I’ve entered Crazy Mountain 100 this year as my qualifier. There are so many strong women in my age group! It’s very difficult to stay in the sport when every cell in the body wants you to stop. Keep doing the research and include women in my age group. I’m happy to participate if needed. Thank you also for your work and the article.

Donna Arrington

It’s nice to see some articles about older runners. I’m turning 70 this August, and I’m planning a trail marathon this summer, and then hopefully an Ultra in late fall or early winter. I have definitely slowed down, but I am so thankful for every run I take. Thanks for the information and inspiration Ken, and good luck Ed !

Thank you for the editors note recognizing Gunhild’s accomplishment. She never should have been left out

What’s even more dramatic is the dropoff in sub-24 hour finishes. I made a chart a while back showing this. Using results back to 1985, it’s 12 runners at age 60, 6 at age 61, 3 at 61, 1 at 62, and none older than that with the exception of Ray Piva at age 68!

* 3 at 62, 1 at 63

Age happens, prepare to welcome it. But regardless of athletic ability , healthy diet, passion for workouts and love of the race community what sidelines or dramatically slows down so many older, 65+ , athletes is simply age. The older you are the more likely a serious injury , a heart arrhythmia, cancer or who knows what. Yes younger folks are susceptible as well but with each passing decade the odds of staying healthy and being an active endurance athlete diminish. The older body just loses its resilience, no matter how much one trains As a 73 yr old triathlete, trail and road runner that’s my experience.