Most young runners have heard the name, but not many know the full story. Older runners wonder about the future of the sport and hope to preserve our community, but few understand how running became what it is today. The answer, in large part, comes down to one man.

Listen to Buzz’s interview with Frank Shorter here.

Frank Shorter stood at the pivotal points that shaped the very foundation of modern running. Understand what Frank did, and you’ll understand not just the sport, but the culture that’s grown up around it.

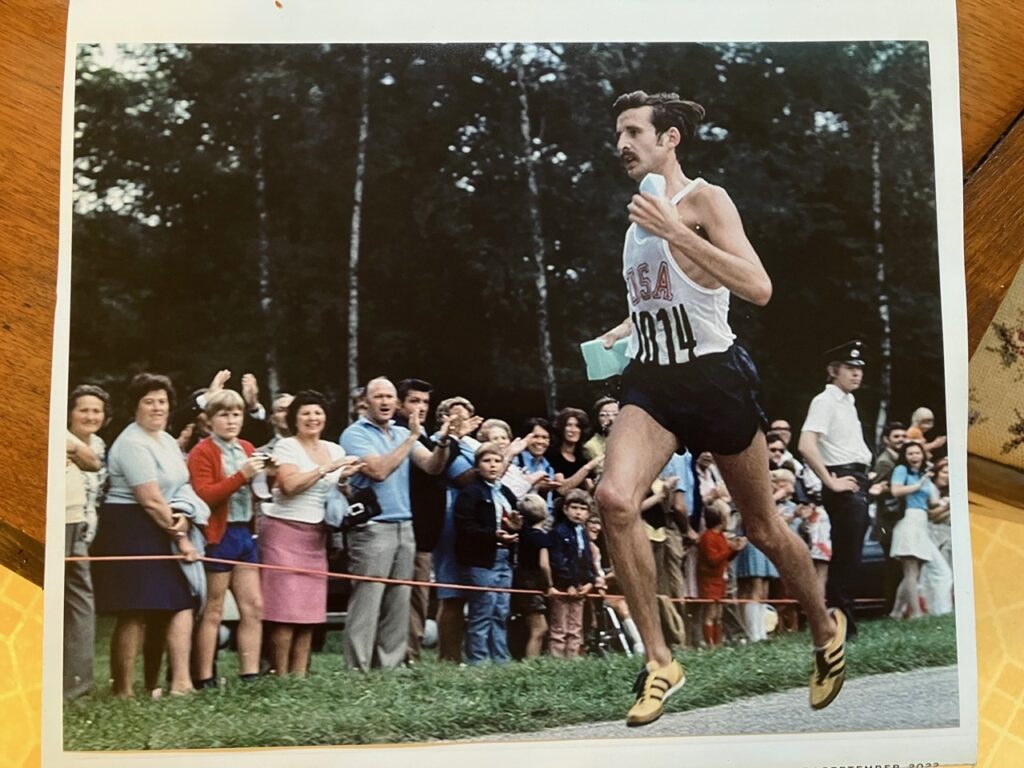

In 1972, at the Munich Olympics, Frank Shorter threw down a blistering 4:33 mile nine in the marathon. He surged away from the field and never looked back, winning gold for the U.S.—the first for an American marathoner in the modern era. Still, the only American man, though Joan Benoit Samuelson would join him in 1984 as the only American woman to win gold. Shorter would later say, “I floored it, just as I’d rehearsed during my time trial the week before… My opponents were surprised but not impressed. What they didn’t know was my capacity for riding my pain.”

The result? A running boom like the world had never seen. Before Frank, running was a niche pursuit. People ran track in school, then hung up their spikes. There were no fun runs, no lotteries for popular races, and certainly no running specialty stores. Frank’s victory changed everything. An estimated 25 million Americans took up running in the 1970s and ’80s, yes, including President Jimmy Carter.

But that race was memorable for another, far darker reason. In the same Olympic Village where Shorter celebrated his gold medal, Palestinian militants from Black September launched a deadly attack, killing Israeli athletes and hostages in what became known as the Munich Massacre. Shorter, who was there, recalled, “I heard the shots. I was sleeping on the balcony, because my roommate Dave Wottle had just gotten married and snuck his wife into our room. After the massacre, I thought we were going home. Nothing is worth a human life.”

Frank was shocked when they still ran the next day, but, he was able to set aside the shock long enough to win the gold medal.

For better and worse, Munich changed the world. The modern age of terrorism arrived, broadcast live on TV. The Games would never feel the same again.

Four years later, at the 1976 Montreal Olympics, Shorter returned as the favorite. This time, though, victory slipped away. He took silver behind East Germany’s Waldemar Cierpinski, who later turned out to be part of the East German state-sponsored doping program. Frank didn’t mince words about it: “There was nothing anyone could do about it. The President of the IOC was a good friend of Erich Honecker, the East German communist President.”

Rather than stew in frustration, Frank channeled his energy into change. He understood that doping wasn’t just an isolated scandal; it was a systemic issue that threatened the integrity of sport itself. More on that in a moment.

First, though, Frank turned his attention to another broken system: shamateurism. In those days, Olympic athletes couldn’t accept a dime without losing their eligibility. The ideal of amateurism was romantic in theory, but deeply unfair in practice. Privileged athletes could train full-time, while working-class competitors had to juggle jobs and training, or drop out altogether. Meanwhile, athletes from communist nations were fully funded by their governments while still competing as “amateurs.”

Frank, alongside Boulder attorney Bob Stone and a crew of local athletes, engineered a workaround: the athlete trust fund. Their advocacy led to the passage of the Amateur Sports Act of 1978, a landmark law that finally started to dismantle the amateur-professional divide. It changed the game not just for runners, but for athletes worldwide.

“It was a turning point,” Frank later said. “We facilitated a solution. It was Rich Castro, it was Boulder athletes, it was Bob Stone, it was Steve Bosley with Frank Shorter.”

But Frank wasn’t done yet.

By the late ’90s, doping had become endemic. The IOC did little to stop it. Once again, Frank stepped up. He helped found the U.S. Anti-Doping Agency (USADA), becoming its first board chairman. In 2001, USADA was recognized by Congress as the official anti-doping body for U.S. Olympic sports. WADA, the global counterpart, soon followed.

Frank described the behind-the-scenes pressure play: “The White House had enough leverage to mandate a world anti-doping agency to be created. They told the IOC the non-profit status of the Salt Lake City Games would be revoked unless the IOC acted.”

Thanks to Frank and his allies, anti-doping rules became a permanent part of sport, and while the battle is ongoing, the culture around clean competition is stronger than ever.

And then, perhaps his most personal act of courage: In 2011, Frank shared publicly that he had endured years of physical abuse as a child at the hands of his father, a prominent physician. The revelation shocked many, but it also resonated deeply. “At about age 8, I started to run,” Frank said. “When I was out there, out of the house, running, he couldn’t get me.”

By speaking openly, Frank helped countless others feel less alone. “I want people to know that abuse knows no socioeconomic status, is more frequent than we realize, and that we can work together to provide environments where children feel safe coming forward.”

Frank Shorter’s legacy is almost too big to pin down: Olympic gold medalist, architect of the running boom, fighter against doping, crusader for athlete rights, and a man brave enough to share his most painful truths. Along the way, he also founded a sportswear company, covered races as a television commentator, and, yes, attended law school while winning Olympic gold, because as Frank once quipped, “If it ever comes down to sleeping under an overpass, or practicing law … I’d have a backup.”

Today, Frank Shorter is 77. He still gets out for a daily run or walk, and, as he puts it, he feels blessed. Maybe that’s the final lesson from the man who shaped our sport: you keep moving forward, no matter what.

Fun Facts About Frank

Now, an estimated 621 million people run worldwide. Most aren’t chasing medals, but simply running for the joy, camaraderie, and health of it. Frank Shorter didn’t just win races, he helped build a global community. His influence transcends sport.

Listen to Buzz’s interview with Frank Shorter here.

Thanks for publishing this revealing story about Frank. I admired him greatly as a slightly younger runner whom had the privilege of running with him as did a thousand others in the Cooper River Bridge 10k.

Frank Shorter has been, and always will be. my running idol!

I remember one time, when he was in the Chicago area for commentary of the Chicago Marathon, he was the attraction for a public “fun run” from a suburban New Balance shoe store. There was a heavy thunder storm that evening. Frank opened the front door, looked out at the rain, turned around and said “let’s just stay in and eat pizza.” Myself and about ten other people sat with him, eating pizza, drinking beer and talking running, for over an hour! It was an incredible and unbelievable experience!!

I started running in HS in the 1970s. Frank, along with Boston Billy Rodgers were my running idols. The good old days!

Dennis, Brent, and Martin; thank you for the wonderful personal stories! I have none myself. Only while researching my premise did I look beyond the medals and races, and learn the impactful things he has done for the sport.

We hope to see Frank again at the Indy Mini Marathon this coming Saturday. He’s usually at the line of bricks across the Indy 500 race track with Dave Calabro, Channel 13 sports reporter. Frank is a humble person.